|

|

|

|

|

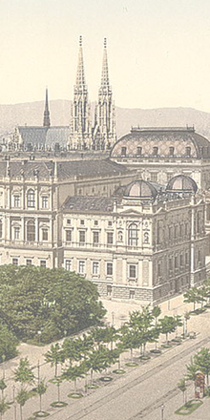

Requiem in ViennaPrologueObservers afterward noted nothing different about the day. Just another typical rehearsal under the new Court Opera Director Gustav Mahler. "The drill sergeant," the singers called him. They were preparing for a performance of Lohengrin and Mahler was particularly fussy about Wagner. A Jew--though he had converted to Christianity before being offered his new position--Mahler walked on Tiffany eggs whenever preparing for one of the Master of Bayreuth’s works, for Wagner was still the darling of the German nationalist press. Upset one of those critics with a single note out of place, a slight misstep in staging, and Mahler would bear the brunt of their "What can you expect from a Jew" level of criticism. So, today, hectoring, hectoring. And there would be a good eight hours of it if the Herr Director's usual routine were followed. The object of his strident complaints this morning was Fräulein Margarethe Kaspar, a young mezzo from the back of beyond in the Austrian region of the Waldviertel, the most unlikely place for a singer to hail from. A pig farmer was more likely the product of that region; a slightly moon-faced, inbred specimen of the human race. Not a soprano at Vienna's Court Opera! Yet here she was, Fräulein Kaspar from Krumau (not even an inhabitant of the so-called city of Zwettl!) in full regalia for her role as one of the four pages in Wagner's adaptation of the medieval German romance. Her heavily rouged lips were trembling; she was near tears. "You're singing like you're calling in the pigs for slops," Mahler shouted at her. "Please do not make me regret my decision to sign you." It was later reported that at that point the poor girl broke into the tears which had been accumulating, waiting for egress; that her otherwise creamy complexion turned a quite unattractive blotchy, mottled red at the cheeks, and she cupped her rather tiny hands over her face in shame. "My god, woman," Mahler thundered on. "Do compose yourself. This a profession, you know. If you haven't the skin for it, go back to your rustic simplicity and the local boys with their thick hands." This last was said with Mahler standing not a hand's length from the young girl, yet his comments carried to the last row of the balcony. A sudden hush went over the entire cast; even the cacophonous tuning of the orchestra in the pit and last-minute backstage hammerings were stilled. This was too much, and even Mahler seemed to realize he had overstepped the bounds of propriety. He drew closer and wrapped a protective arm around the girl --who was rumored to be his mistress, of course. She was of no great size; still, she stood half a head over the diminutive Director, who was five feet and four inches in his scuffed leather boots. "There, there, Grethe." He patted her shoulder, attempting rather unconvincingly to console the young girl. "I am sorry to shout at you so. But the high C must be hit, not simply approached. Essential, quite essential." Then he left her, still sobbing, turning back to the rest of the opera chorus. "What are you all gaping at? Back to work." He clapped his hands, an insistent schoolmaster. At that very instant came a shout from behind the partially curtained stage. "Watch out!" It was too late, however, for the heavy asbestos fire curtain, its hem filled with lead weights, came crashing down. It hurtled onto the unfortunate Fräulein Kaspar, who was still weeping into her cupped hands. The curtain narrowly missed Mahler, who dove out of the way. The curtain hit the stage with a fearful crashing, after which there was a moment of stunned silence. Only the black patent leather shoes of the fallen soprano were to be seen from under the curtain. Then came shouted voices from stagehands behind the curtain, one carried above the others: "She's dead. By god, the little song bird's dead and gone." |

||